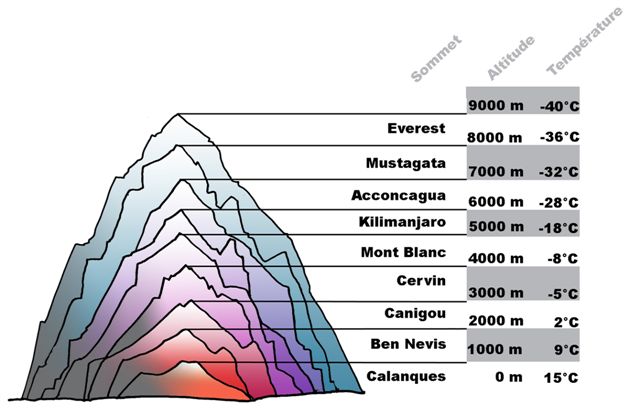

There is very little data available to determine the effect of high altitude on young children. Sex, Age and fitness level do not appear to play a role in who will get altitude sickness. The largest concern for travellers to high altitudes is hypoxia (not being able to get enough oxygen) due to decreased air pressure, low humidity and cold. There is the possibility of severe and fatal symptoms as the sickness can affect your lungs and brain. Symptoms for altitude sickness vary from mild to severe and can include: severe headache, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, fatigue and insomnia. Mild symptoms can resolve once the traveller has been acclimatized to the altitude. Travellers should not push past their limits. The best way to prevent altitude sickness is to ascend slowly to give your body time to adjust to the changes in oxygen. It is often described as feeling like a bad ”hangover”. If you suspect the onset of HACE or HAPE, evacuate rapidly to a lower altitude (descending at least 1,000 to 1,500 feet) and get evaluated by a physician as soon as possible.Altitude sickness is commonly experienced when travellers go from a low altitude to higher altitude of 2100m (7,000 ft) above sea level. Hydration: To offset increased fluid losses at high altitudes, stay well-hydrated.Įvacuation: Stop ascending until AMS symptoms resolve. Proceed higher during the day, but return to a lower elevation to sleep (climb high, sleep low).Īppropriate exercise level: Until acclimated, exercise moderately, avoid intensity, and be alert to shortness of breath and fatigue. When starting out higher than 9,000 feet, spend two nights acclimating to that altitude before proceeding higher.

Increase no more than 1,000 to 1,500 feet per day. Staged ascent: If possible, your first camp should be no higher than 8,000 feet. Improve your fitness with regular hikes while carrying a load in anticipation of your climb. Preparation: Discuss your planned climb with your health care provider while undergoing a pre-participation exam (Part C of the Annual Health and Medical Record). The cough may become productive and with frothy sputum early on that may turn reddish. Shortness of breath becomes more pronounced, with chest pain as fluid collects in the lungs. HAPE symptoms often appear initially as a dry cough, soon followed by shortness of breath, even at rest. Signs and symptoms often include a severe headache unrelieved by rest and medication, bizarre changes in personality, seizures, and coma. If the illness progresses, descent is needed.īe watchful for loss of coordination (e.g., an inability to walk a straight line or stand straight with feet together and eyes closed). Continuing to ascend in the presence of symptoms is not recommended. The treatment is to descend or to stop ascending and wait for improvement before going higher. Have you recently arrived at an altitude of 6,000 feet or higher? Look for signs of AMS, such as headaches, loss of normal appetite, nausea (with or without vomiting), insomnia, and an unusual weariness and exhaustion. GENERAL INFORMATION Acute Mountain Sickness As altitude is gained, air grows “thinner,” and less oxygen is inhaled with each breath.

These trips might result in symptoms or effects of acute mountain sickness (AMS), high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), or high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), which if untreated could result in death. Are you getting ready for your Philmont Trek and a summit of Baldy Mountain? Perhaps you live close to sea level and plan to hike the John Muir Trail in the Sierra Nevada range, Kings Peak in the Uinta range, or some 14ers in Colorado.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)